“Today you can find it in any well-equipped electronics lab, although it is still bulky. “Thirty years ago only military suppliers had the equipment necessary to do the electromagnetic analysis involved in this attack,” Kuhn says. The monitor refreshes its image 60 times or more each second averaging out the common parts of the pattern leaves just the changing pixels-and a readable copy of whatever the target display is showing. Kuhn, a computer scientist at the University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory, demonstrated that even flat-panel monitors, including those built into laptops, radiate digital signals from their video cables, emissions that can be picked up andĭecoded from many meters away. Many people assumed that the growing popularity of flat-panel displays would make Tempest problems obsolete, because flat panels use low voltages and do not scan images one line at a time. Without Tempest shielding, the image being scanned line by line onto the screen of a standard cathode-ray tube monitor can be reconstructed from a nearby room-or even an adjacent building-by tuning into the monitor’s radio transmissions. In the 1960s American military scientists began studying the radio waves given off by computer monitors and launched a program, code-named “Tempest,” to develop shielding techniques that are used to this day in sensitive government and banking computer systems. Spies connected rods in the ground to amplifiers and picked up the conversations. In World War I the intelligence corps of the warring nations were able to eavesdrop on one another’s battle orders because field telephones of the day had just one wire and used the earth to carry the return current. The idea of stealing information through side channels is far older than the personal computer. The experts are sure of only one thing: whenever information is vulnerable and has significant monetary or intelligence value, it is only a matter of time until someone tries to steal it. Such attacks also leave no anomalous log entries or corrupted files to signal that a theft has occurred, no traces that would allow security researchers to piece together how frequently they happen.

Side-channel attacks exploit the unprotected area where the computer meets the real world: near the keyboard, monitor or printer, at a stage before the information is encrypted or after it has been translated into human-readable form. Yet that approach can secure only information that is inside the computer or network. Outside of a few classified military programs, side-channel attacks have been largely ignored by computer security researchers, who have instead focused on creating ever more robust encryption schemes and network protocols. Even certain printers make enough noise to allow for acoustic eavesdropping. Technically sophisticated observers can extract private data by reading the flashing light-emitting diodes (LEDs) on network switches or by scrutinizing the faint radio-frequency waves that every monitor emits.

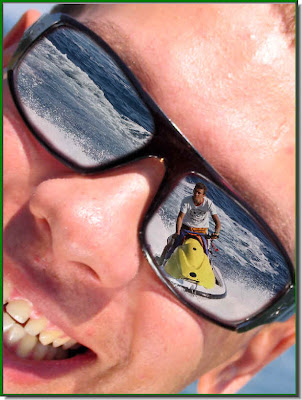

GLASSES REFLECTION SOFTWARE

Researchers recently demonstrated five different ways to surreptitiously capture keystrokes, for example, without installing any software on the target computer. The reflection of screen images is only one of the many ways in which our computers may leak information through so-called side channels, security holes that bypass the normal encryption and operating-system restrictions we rely on to protect sensitive data. The mere act of viewing information can give it away. Spectacles work just fine, as do coffee cups, plastic bottles, metal jewelry-even, in his most recent work, the eyeballs of the computer user. In experiments here at his laboratory at Saarland University in Germany, Backes has discovered that an alarmingly wide range of objects can bounce secrets right off our screens and into an eavesdropper’s camera. The image that seems so legible is a reflection off a glass teapot on a nearby table. Not only is the laptop 10 meters (33 feet) down the corridor, it faces away from the telescope. Through the eyepiece of Michael Backes’s small Celestron telescope, the 18-point letters on the laptop screen at the end of the hall look nearly as clear as if the notebook computer were on my lap.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)